This brief is the second in a series giving an overview of Pennsylvania's fiscal affairs.

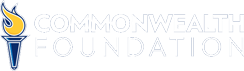

The state constitution tasks the legislature with both raising and spending revenue. Over time, however, this simple plan has been disfigured. Today less than half of revenue is under direct legislative control. The legislature must consolidate and control revenue instead of letting it flow to programs automatically through a confusing maze of accounts.

The Pennsylvania government funds its operating budget through at least 26 major revenue sources that totaled $86 billion last year. Under Article III of the constitution, all bills for raising revenue are supposed to originate in the House of Representatives, and payouts of public money are supposed to occur only after an appropriation.1 Today, however, a majority of state revenue comes from the federal government and from special-purpose state funds, meaning it gets raised and spent according to formula and administrative rule rather than legislative action. Additionally, dependence on these alternative revenue sources is growing.

Thirty five percent of state operating revenue comes from the federal government. Most non-federal revenue comes from various taxes. The remaining one-fifth of operating revenue comes from what are marked in the annual Governor’s Executive Budget as simply “Other Funds” but are more accurately called special purpose funds. These are monies taken in by a network of at least 150 special purpose state entities with their own revenue streams. The Public Transportation Trust Fund, for example, received $450 million in statutory payments from the Pennsylvania Turnpike last year.

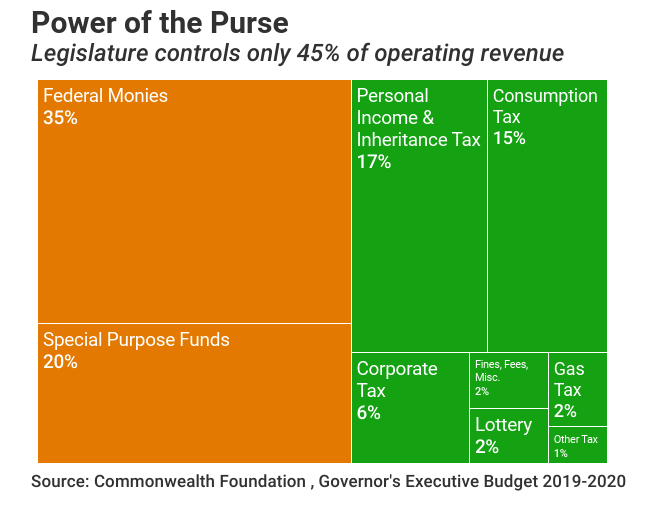

Excluding federal monies and monies drawn from the special revenue funds, the state’s largest revenue item is the personal income tax ($14 billion in projected collections this year according to the Governor’s Executive Budget), followed by the sales and use tax ($11 billion). Most other state revenue streams are $1 billion or less in size. This includes payments from the state liquor monopoly, the Liquor Control Board. For all the talk of the liquor monopoly as an important earning asset of the state, and all the resistance to its privatization, it remits to the state only $185 million of profit per year, which is two tenths of one percent of the operating budget. Liquor sales do generate significant tax revenue, but the same taxes would also be collected under a private liquor control regime.

Detail of key taxes and fees include the following:

- Personal Income Tax: 3.07% on household and proprietor earnings

- Sales and Use Tax: 6% charge on the retail sale, consumption, rental or use of tangible property and information. Food, most clothing and other items are excluded.

- Corporate Net Income Tax: 9.99% on profits of corporate business activity occurring in Pennsylvania, as determined by an apportionment formula.

- Liquid Fuel Taxes: $0.576 per gallon on motor gasoline, with different rates for other types of transportation fuel

- Gross Receipts Tax: 4.5% on revenue earned from certain transportation, telecommunication and energy services. Some revenues are subject to 0.5% additional tax.

- Cigarette Tax: $0.13 per cigarette

- Inheritance Tax: 4.5% on the transfer of a deceased person’s property to lineal family, 12% on transfers to siblings, 15% on transfers to others. Transfers to surviving spouse are not taxed.

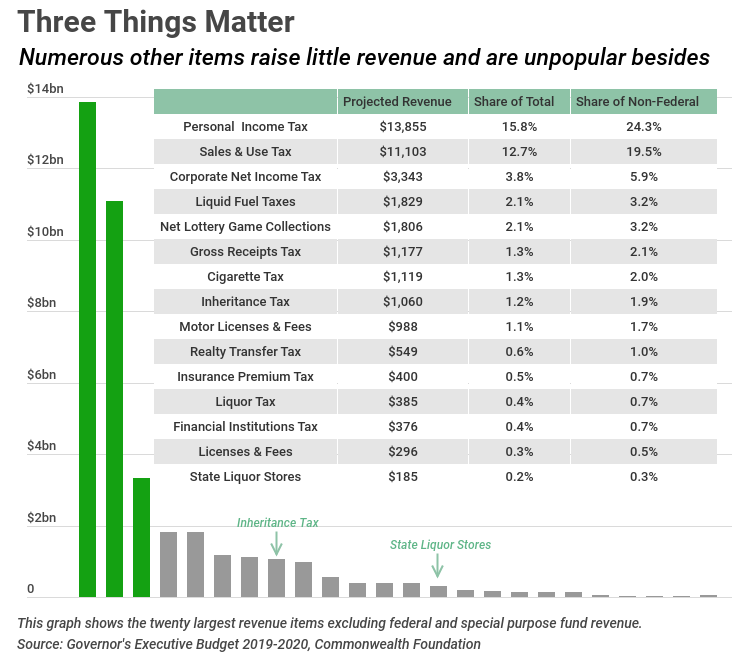

Tax collections generally flow to one of three state accounts:

- The General Fund, by far the largest account, receives all personal and corporate taxes as well as other revenues such as state liquor revenue and a variety of fees. It funds most legislatively appropriated expenses.

- The Motor License Fund receives gas tax and motor license revenue: most of these moneys can be appropriated only for transportation.

- The Lottery Fund receives lottery revenue: the majority of these funds are spent on services for the poor or infirm elderly.

From each of these funds (hereafter “core funds”), appropriations are made to various expense items. Monies from the core funds are largely unencumbered and free for legislative appropriation, but this has begun to change over the years, as small portions have been designated for automatic transfer to special purpose funds. Diversions of core revenue include:

- 0.947% of sales and use tax receipts go to the Public Transportation Assistance Fund

- 4.4% of sales and use tax receipts are transferred annually to the Public Transportation Trust Fund.

- $30.73 million annual transfer of cigarette tax collections to the Children’s Health Insurance Fund and $23.49 million annual transfer to the Agricultural Conservation Easement Purchase fund.

- Sales taxes will be transferred automatically if needed to pay the debts of the Commonwealth Financing Authority

Such monies are effectively removed from the regular appropriation process and redirected to pre-determined uses. The Governor’s Executive Budget breaks down state programs by funding source, which, with some compilation and reorganization, allows for an estimate of which revenue streams fund which purposes.2 Commonwealth Foundation estimates are shown in the flow chart below.

Health and Human Services is funded about 50/50 by federal and state revenue due to the structure of the Medicaid program, which was conceived at the federal level to be a system whereby state spending would be matched with federal dollars. Unfortunately, this is a recipe for cost laxity: it becomes very easy to spend when somebody else is paying a large portion of the bill. Indeed, Medicaid costs are among the largest and fastest growing parts of the budget.3 Such a funding structure has also led to questionable schemes designed to draw in more federal money such as the Quality Care Assessment, where the same hospitals paying the state assessment (tax) receive large amounts of federal funding.4

Certain policy priorities: Health and Human Services, Economic Development, Transportation (specifically, mass transit) and Recreation and Cultural Enrichment (largely environmental spending) are disproportionately funded by Federal money and special funds. Legislators have put these programs on “auto pilot” by design to defend against their dismantling by political opponents. It is far more difficult for a future legislature to dismantle spending that receives dedicated funds than to simply not appropriate the money. A future legislature must proactively enact new legislation to reverse the earlier automatic funding or shut down the special purpose entity. Otherwise money will continue to flow.

Dependence on federal and special funds has been growing, and consequently legislative control over spending has been shrinking. Tax revenue, the revenue stream that the legislators actually appropriate from year to year, has lagged total budget growth over the past five years. Federal money and special-purpose state money have made up the gap.

For the purpose of expense control, transparency and responsive governance it is important that the state legislature re-assert fiscal primacy. Revenue streams properly belonging to the three core government funds (General, Motor License and Lottery) should not be sent by formula to special-purpose funds for non-discretionary use. Revenue currently collected outside of the core funds (For example: turnpike income, gaming revenue, and tobacco lawsuit monies to the extent permitted under the settlement), should be brought under legislative control. Changing direction starts with switching off the autopilot.

Notes:

1.Pennsylvania Constitution. Article III, Section 10: “Revenue Bills” and Article III Section 24: “Paying out Public Moneys.”

2. Unfortunately the Budget Office’s overly-broad “programs” do not line up with the more specific expense items analyzed in Part I. Health and Human Services, for example, could be helpfully split up into several more specific categories. “Economic Development” can mean nearly anything.

3. “Slicing Pennsylvania’s Finances, Part I: Spending is Overgrown and Unsustainable.” Commonwealth Foundation Policy Brief. August 21, 2019.

4. “Hidden Human Services Spending.” Commonwealth Foundation Policy Blog. June 27, 2018. Readers interested in the pernicious influence of federal funding on state and local programs generally should read the Cato Institute report on the topic “Restoring Responsible Government by Cutting Federal Aid to the States.” Policy Analysis No. 868, May 20, 2019.