Jim Cimerol’s pub in Catasauqua is struggling to survive, but this isn’t unique in Pennsylvania, where thousands of bar owners and employees languish because of the state’s unyielding COVID-19 mitigation measures.

Passed last month with bipartisan support, House Bill 2513, seemed like a reasonable solution to the restaurant industry’s ongoing crisis. The bill, sponsored by state Rep. Garth Everett, would boost all restaurant capacity to 50 percent, end requirements to order food with an alcoholic beverage, and permit alcohol sales past 11 p.m. Governor Tom Wolf, however, issued a veto. According to Gov. Wolf, “By eliminating these critical protections, in addition to removing certain limits related to bar service and purchasing of alcoholic beverages, this bill increases the likelihood of COVID-19 outbreaks.”

And yet, only 6 percent of individuals who reported to contact tracers between July and October had confirmed visiting a restaurant 14 days before the onset of symptoms. In other words, Gov. Wolf’s dire presentation doesn’t match reality.

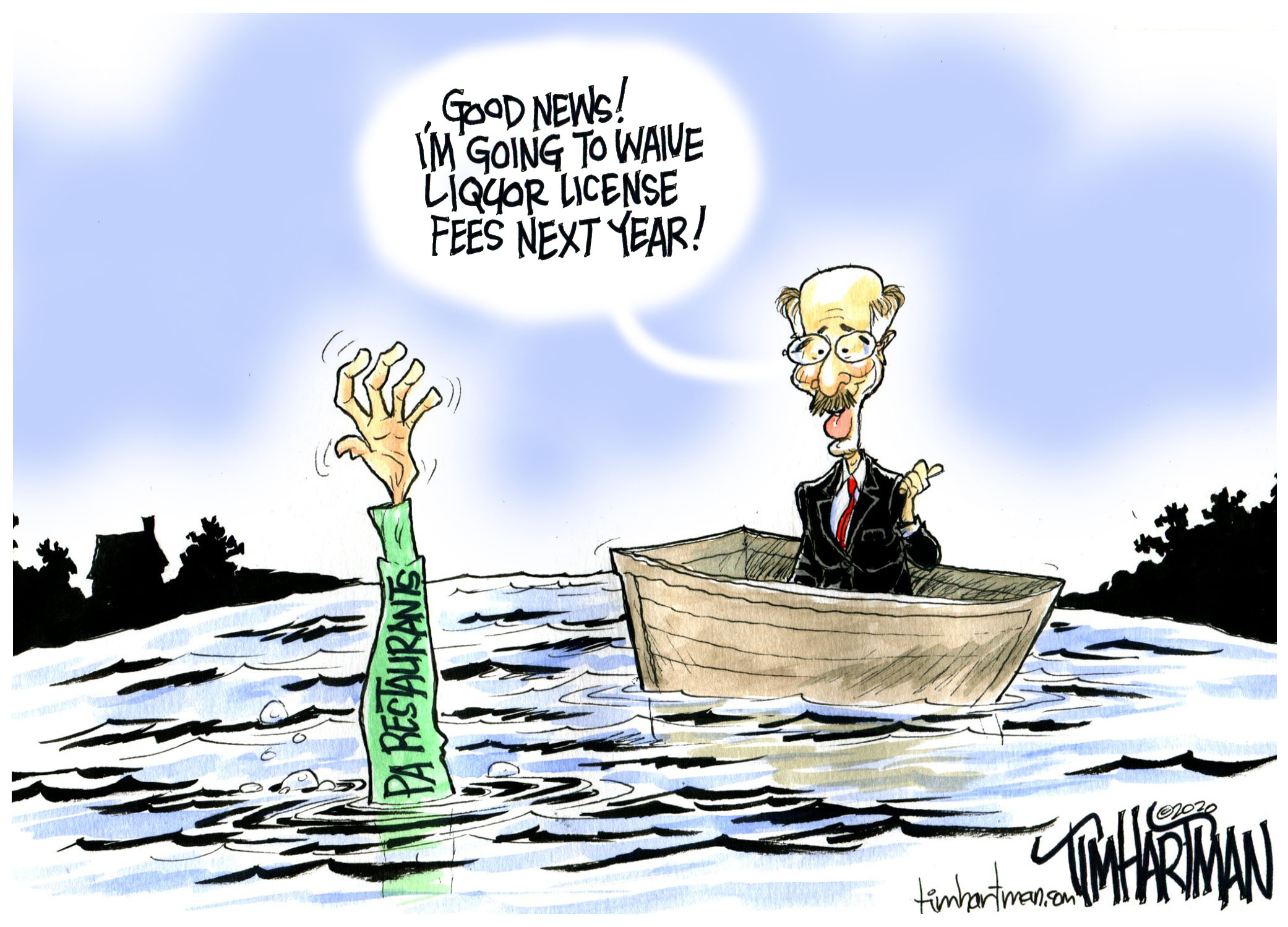

Clearly, Gov. Wolf looks out of touch—and perhaps he knows it. Last week, following his veto, he released a proposal to waiver license fees collected by the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB) in January 2021.

Of course, an estimated $20 million back in the budgets of 16,000 restaurants and bars is welcome, but nowhere close to replacing the income they’ve lost. Just ask Pennsylvania’s restaurant owners. “It’s not going to help me,” said Jim. “Open my place back up, that’s what’s going to help me.”

Indeed, if Gov. Wolf supports lightening restaurants’ regulatory burden, he should work to privatize the PLCB. House Bill 2457, sponsored by Rep. Timothy O’Neal, would fully privatize Pennsylvania’s retail and wholesale liquor sales, creating more choice and convenience for state residents, along with bar or restaurant owners stocking their businesses.

In addition, House Bill 1469—also sponsored by Rep. Timothy O’Neal—and Sen. Pat Stefano’s Senate Bill 880 would allow wine and spirits to be sold by restaurants and hotels. Meanwhile, Sen. Gene Yaw has introduced Senate Bill 548, which would create a franchise store system.

Here are four ways the PLCB works against Pennsylvania businesses:

1. Liquor licenses are expensive, costing as much as $500,000. Licenses are limited to 1 per 3,000 residents in a county. And not all restaurants that would like to serve alcohol are able to do so. As it stands, Pennsylvania’s per-capita limits are the 8th lowest in the nation.

2. Local restaurants are burdened with artificially high prices. As of 2018, the average PLCB markup on spirits was 65 percent, with only a 10 percent discount for licensees.

3. PLCB doesn’t deliver. The bureaucracy requires restaurants to pick up their orders at PLCB warehouses while private wholesalers offer delivery.

4. Ordering Special Liquor (alcohol not regularly stocked by PLCB) is logistically challenging. Over 1,200 wine and liquor products in Pennsylvania are only available through a special liquor order (SLO). This spring, distributors sued the PLCB for a moratorium on orders, which must be delivered to a PLCB warehouse. But when the PLCB shut down, private distributors couldn’t operate—even though they were deemed essential. The lawsuit also highlighted PLCB’s refusal to comply with a 2016 law allowing delivery of wines directly from private distributors.

Adding insult to injury, three weeks ago, the PLCB online ordering system malfunctioned, leaving establishments unable to order for days. This is just the latest in a long established pattern of PLCB failures.

As restaurants navigate an uncertain future, now is the time to give restaurants and bars permanent relief from the archaic and burdensome PLCB.

RELATED : JOBS & ECONOMY, PRIVATIZATION, LIQUOR STORE PRIVATIZATION